Pour une restructuration organisée de la dette publique sénégalaise en 2026 (Par Seydina Ndiaye, Économiste, Banquier d’affaires)

Faced with the daunting debt burden, symbolized by 30% of GDP needing refinancing, and the imperative to find 6,075 billion CFA francs by 2026, a consensus seems to be emerging: a growing number of economists and financial experts believe that debt restructuring in Senegal is now inevitable. A clear, well-structured, and coherent roadmap would help avoid the chaos of a disorganized restructuring and, above all, a liquidity crisis.

Senegal is on the brink of an unprecedented liquidity crisis. With a financing need of 6,075 billion FCFA in 2026, a public debt reaching 132% of GDP according to the IMF, and a projected debt service of 5,500 billion FCFA, the country faces a refinancing wall that threatens its macroeconomic stability. The failure of the agreement with the IMF on November 6, 2025 (see the IMF press release accessible via link (2)), coupled with the series of bad news since then, triggered a bond market crash on international markets, with Eurobonds trading at discounts of up to 49%. In this unstable context, a strong and objective conviction is essential: debt restructuring is no longer an option, but a strategic necessity to avoid a disorganized default with devastating economic and social consequences. This strategic note proposes a roadmap leading to an organized restructuring of Senegal's debt by 2026, drawing on the lessons learned from the experiences of Ghana and Ethiopia, while avoiding the catastrophic scenario that Lebanon experienced in March 2020.

The proximity of a tipping point: March 2026

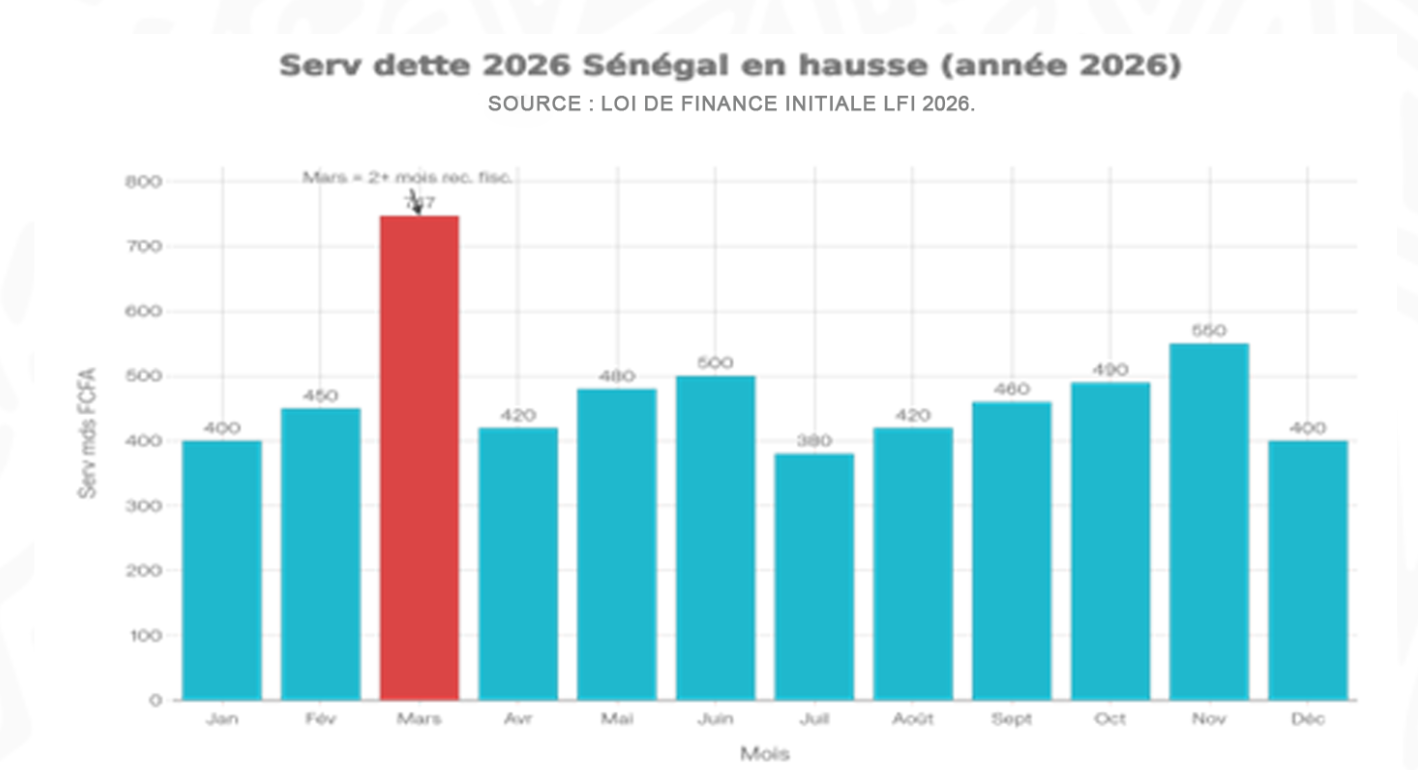

Analysis shows that March 2026 represents the critical breaking point in Senegal's debt trajectory. Debt servicing will reach a record 747 billion FCFA that month, equivalent to more than two months of tax revenue (February 2025 + March 2025 = 671 billion FCFA). This burden literally crushes the State's repayment capacity, especially since average monthly tax revenue is around 340-360 billion FCFA.

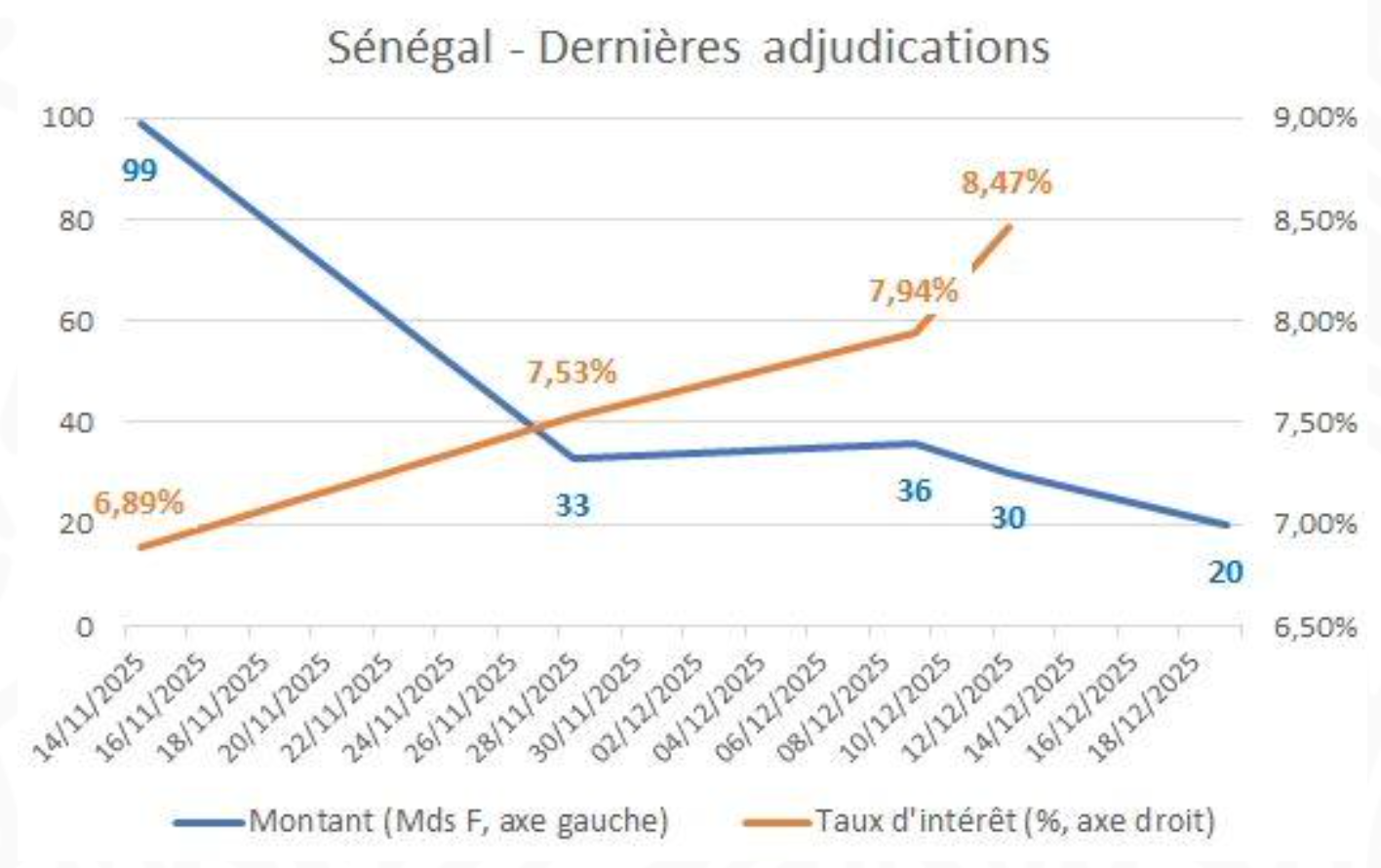

Furthermore, the most critical deadline will be March 13, 2026, when Senegal must repay €333.3 million (219 billion CFA francs) on Eurobonds issued in 2018. To cope with this peak, the government plans to raise 810 billion CFA francs on the domestic market in March 2026, a highly unrealistic objective given the current tensions in the WAEMU regional market. Indeed, the regional market is already showing worrying signs of saturation. Between December 12 and 19, 2025, subscription rates at auctions fell to 102.4% and then 100.8%, while the weighted average yield skyrocketed from 6.89% to 8.47%, a dizzying increase of 158 basis points in just one month. On December 12, out of an amount of 95 billion FCFA scheduled, only 35 billion were actually mobilized, revealing a rationing mechanism fueled by growing doubts about Senegal's sovereign risk.

This context of extreme financial stress makes the probability of a technical default in March 2026 extremely high in the absence of proactive restructuring. The arithmetic is undeniable: with monthly resources of 340-360 billion FCFA and a need of 747 billion, the financing gap reaches 387-407 billion FCFA for the month of March alone.

A restructuring of external debt is almost inevitable

International financial markets have already made their decision: the hope of avoiding restructuring is now close to zero. Current valuations of Senegalese Eurobonds fully reflect the anticipation of an imminent default.

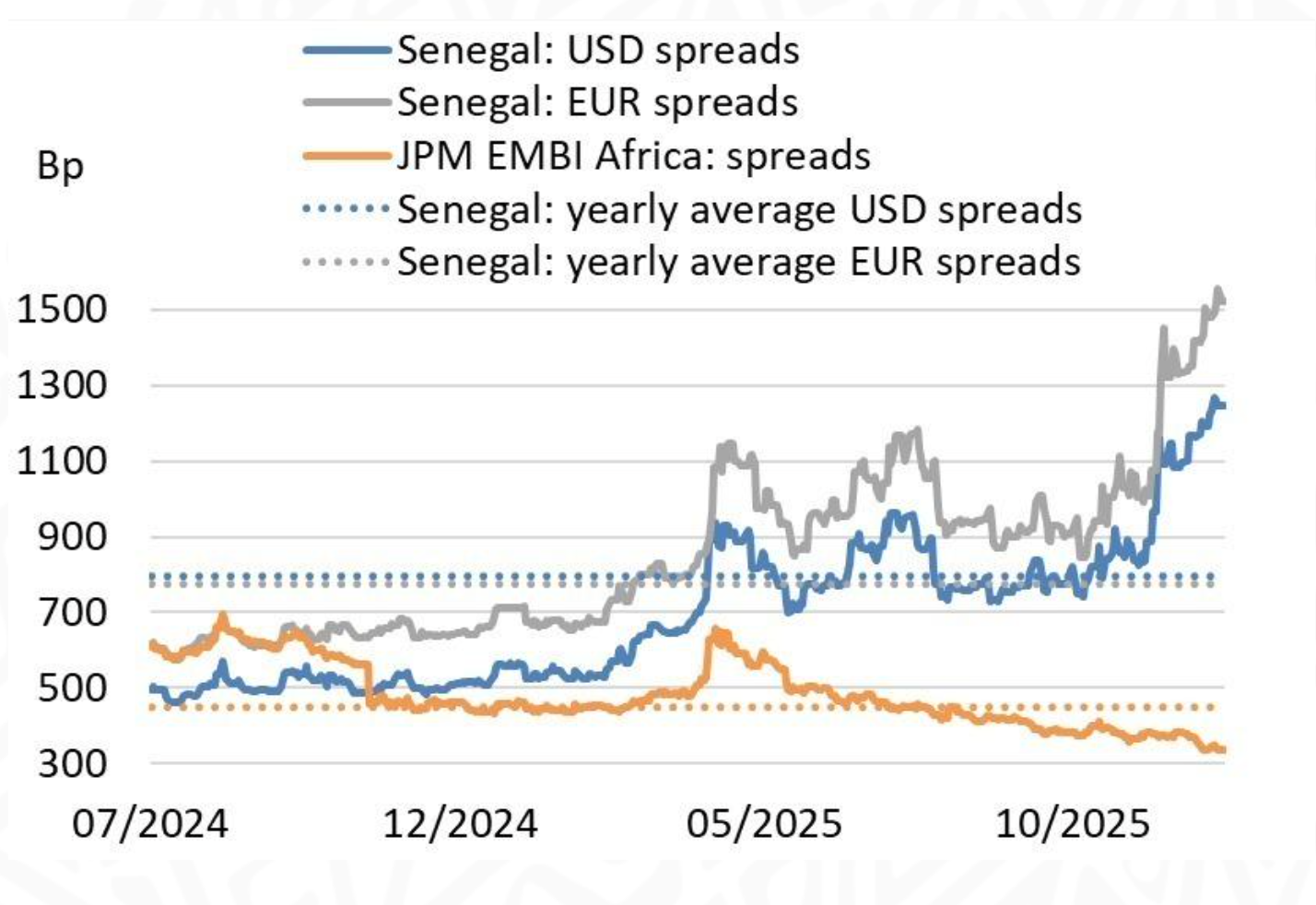

Senegalese Eurobonds have lost approximately 20% of their value in three months, falling below 60 cents for some maturities, signaling market anticipation of default. The 2048 Eurobond is trading at 51 cents per euro, a discount of 49%. The 2037 Eurobond is trading around 52 cents, while even the 2028 maturity, whose repayment is due to begin in March 2026, is trading at a discount of over 30%. Even more telling, commercial loans maturing in February 2026 are trading at a 20% discount, an unequivocal sign that the market has priced in a very short-term default. In just three months, between September and December 2025, Senegal's Eurobonds lost approximately 20% of their value. This bond market crash followed the failure of the IMF disbursement agreement, formalized on November 6, 2025, and the subsequent statement by the Prime Minister on November 8 regarding Senegal's refusal of a restructuring. Until this event, the market still held onto hope for IMF intervention. However, the absence of a disbursement program and the aforementioned statement have irreversibly shifted market sentiment.

Furthermore, the spreads on yields of Senegalese bonds on the international market have doubled, rising from an annual average of 800 basis points in both USD and EUR to 1,500 basis points. Spreads at or above 1,000 basis points make access to the primary market very expensive, even unrealistic for new issuances under normal conditions, hence the closure of the international financial market, which has now been observed and integrated, despite the Eurobond issuance forecasts in official documents.

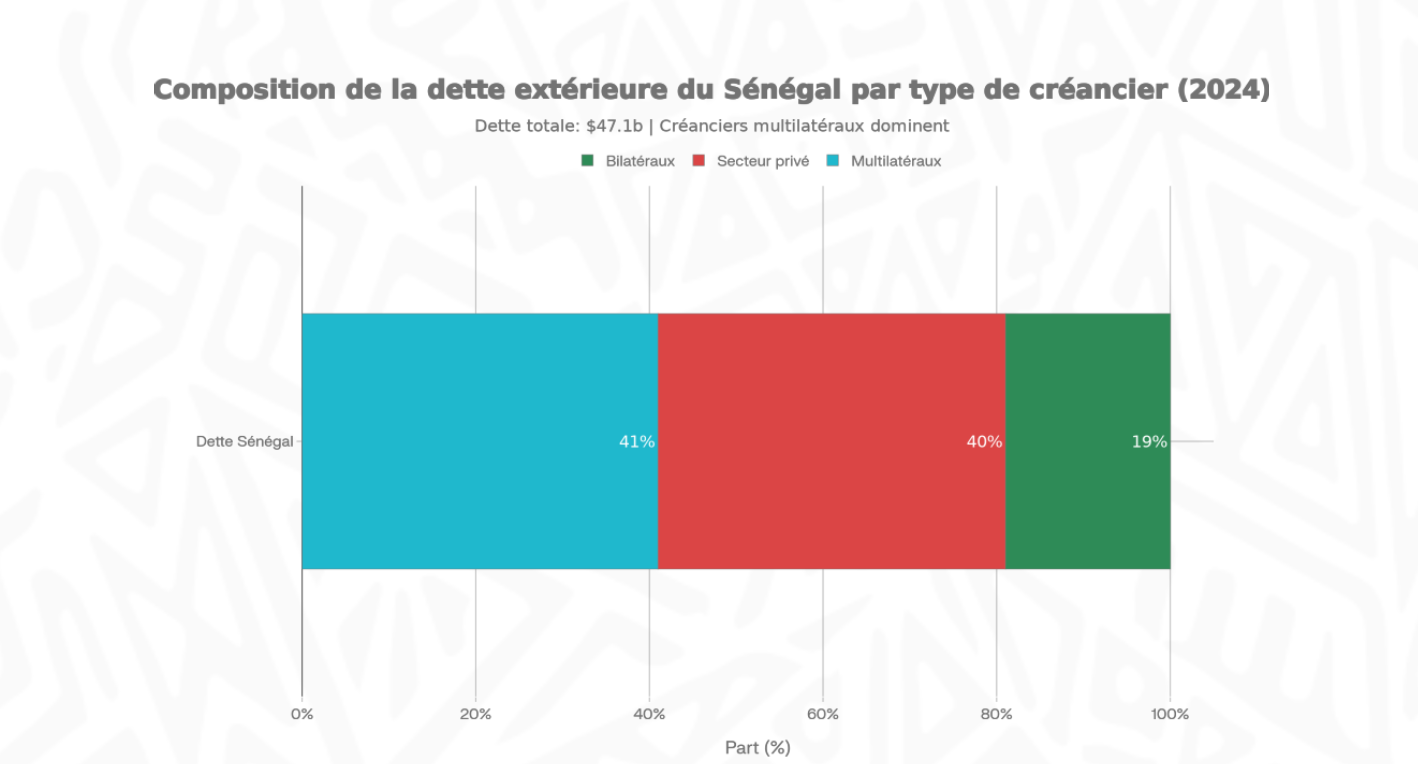

Similarly, Bank of America's (BoA) analysis, particularly regarding the subscription of Total Return Swaps (TRS)—derivative products intended to hedge against default risk on commercial debt—confirms this negative market expectation. Likewise, the research paper by Artisan Partners' EM InSignts team (6) explicitly predicts a likely default by Senegal in the second quarter of 2026. Furthermore, the structure of Senegal's external debt would make restructuring particularly complex. Of a total outstanding amount of $47.146 billion (26,540 billion CFA francs) at the end of 2024, the debt is distributed among multilateral creditors (41%), the private sector (40%), and bilateral creditors (19%). [6]

Senegal's external debt of $47.1 billion is dominated by multilateral (41%) and private (40%) creditors, making restructuring complex but necessary. External commercial debt, which represents 38% of total external debt, is held one-third in Eurobonds, with the remainder held by major financial players such as Standard Chartered, MUFG, and Cargill.7 This concentration among sophisticated creditors could complicate any negotiations in the event of restructuring, but also offers the opportunity for more effective coordination than with a highly fragmented bond market; we will return to this point in Part Two. Thus, the external debt-to-exports ratio reaches 573%, meaning that Senegal would theoretically need nearly six years of exports to cover its external debt. Debt servicing in 2024 represented 42% of exports and 11% of gross national income, unsustainable levels that absorb a disproportionate share of national resources at the expense of productive investment and social spending.

The restructuring already underway on regional debt

While the restructuring of external commercial debt remains to be formally organized, that of regional debt has already begun implicitly through the mechanism of Public Offerings (POs). During the debates on the 2026 budget, the Minister of Finance acknowledged that POs served to "address the problematic branch of bank debt" revealed by the Court of Auditors' report of February 2025. At the end of 2024, this bank debt – subscribed by the State outside of traditional budgetary channels – represented a colossal outstanding amount of 2,150 billion FCFA (9), or 9.1% of the total debt of the central government. Some loans were immediately due, and banks began sending repayment requests for several hundred billion FCFA, creating a threat of an immediate cash flow crisis. (10)

To avoid this liquidity crisis, the authorities and banks opted for an "active debt management" solution: converting a portion of bank debt into bonds during the EPAs (Economic Partnership Agreements). As the Director General of Public Debt explained on December 5, 2025, without this solution, banks would have had to downgrade these receivables and set aside provisions, posing serious solvency problems for the banking system. However, this solution comes at a high opportunity cost. For the first three operations, debt conversion amounted to 585 billion FCFA (according to the Minister), compared to a total amount issued of 1,234 billion FCFA (including the exercise of the over-allotment option). "New money," meaning the fresh funds actually raised, represented only 53% of these issuances, or approximately 240 billion FCFA per EPA on average (11). The crowding-out effect on financing the economy is evident. Senegalese banks, forced to massively absorb sovereign paper, are reducing their lending capacity to the private sector.

This heavy concentration of bank portfolios on sovereign risk triggered the downgrade of the Senegalese banking system's rating by Fitch Ratings on December 8, 2025. The Senegalese banking system was lowered to CCC+, perfectly aligned with the sovereign rating (12). This negative spiral illustrates the contagion of sovereign stress to the financial sector, a phenomenon which, if left unchecked, could lead to a systemic banking crisis. The non-performing loan ratio had already reached 10.6% at the end of August 2025, above the WAEMU average, mainly due to persistent cash flow problems in public enterprises.

An outline of a roadmap for organized restructuring

The benchmark of Ghana and Ethiopia

Recent experience in sovereign debt restructuring in sub-Saharan Africa offers two contrasting case studies that shed light on the strategic choices to be made for Senegal: the relative success of Ghana and the persistent difficulties of Ethiopia.

Ghana successfully completed its restructuring with a 37% haircut in three years, while Ethiopia remains stalled. Senegal should aim for a 50-60% haircut to ensure sustainability.

The Ghanaian model: a phased and comprehensive restructuring

In 2023, Ghana embarked on a comprehensive and ambitious restructuring of its debt, both domestic and external, under a $3 billion, 36-month IMF program. Ghana's approach rests on three complementary pillars.

The first pillar was the restructuring of domestic debt . In September 2023, Ghana completed its Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP) with an impressive 85% participation rate. To mitigate the impact on the banking system, the government established the Ghana Financial Stability Fund with 5.7 billion cedis to support affected financial institutions. This proactive approach averted a systemic banking crisis while restoring the sustainability of domestic debt.

Second pillar: Eurobond restructuring . In October 2024, Ghana finalized the exchange of its $13 billion Eurobonds, with a participation rate exceeding 95%. The final terms involved a 37% haircut on the principal and late payment interest, with two options offered to creditors (13). This restructuring immediately reduced the debt stock by $5 billion due to the principal haircut, in addition to substantial gains on interest payments.

Third pillar: the agreement with bilateral official creditors . Ghana signed an agreement with its Official Creditors Committee (OCC) covering $5.4 billion of bilateral debt. This agreement respects the Paris Club's principle of "comparability of treatment," essential for obtaining IMF approval (14).

The results of this comprehensive approach are tangible. Ghana’s debt-to-GDP ratio fell from 88% to 55% (in net present value) between the start of the restructuring and mid-2025. The agreement with the OCC contributed a 6 percentage point reduction, while the restructuring of Eurobonds provided an additional 10 percentage points. As a result, Ghana successfully completed its fifth IMF review in December 2025, unlocking an additional $385 million, confirming the gradual return of international confidence (15). The cost of this restructuring for investors remains substantial but predictable. The 37% haircut on Eurobonds, combined with extended maturities and reduced coupons, created a significant loss in net present value. Nevertheless, the clarity of the process and coordination with the IMF prevented a prolonged and disorderly default, preserving Ghana’s future access to international markets.

The Ethiopian quagmire: the limits of the Common Framework

Ethiopia, by contrast, illustrates the difficulties inherent in a fragmented and protracted debt restructuring. The country requested debt treatment under the G20 Common Framework as early as February 2021, serving as a test case for this mechanism. Four years later, the restructuring remains incomplete (16). Ethiopia reached an agreement in principle with its OCC in March 2025 for $8.4 billion (approximately 30% of its total external debt of $28.4 billion). This agreement was formalized by a Memorandum of Understanding signed in July 2025, providing for debt relief of over $3.5 billion. The Ethiopian OCC is co-chaired by China and France, reflecting the significant role of Chinese bilateral creditors in the country's debt portfolio (17).

However, negotiations with private creditors remain deadlocked. Ethiopia defaulted on its sole $1 billion Eurobond in December 2023. The government's October 2024 proposal included a haircut of only 18%, with principal repayment between 2027 and 2031 and an interest rate of 5%. This offer was rejected by bondholders, who consider the haircut insufficient and accuse the IMF of exaggerating Ethiopia's economic difficulties. Negotiations have been officially declared deadlocked since October 2025 (18).

This situation creates prolonged uncertainty, which is detrimental to both Ethiopia and its creditors. The lack of a resolution with private creditors prevents the finalization of the IMF program and delays economic recovery. Eurobond holders, meanwhile, remain in default with no clear prospect of recovery.

Lessons for Senegal

The contrast between Ghana and Ethiopia offers three strategic lessons for Senegal:

1. A comprehensive approach is preferable to piecemeal restructuring . Ghana simultaneously restructured its domestic debt, Eurobonds, and official bilateral debt, creating a coherent and definitive solution. Ethiopia, by dealing with its creditors sequentially, became bogged down in endless negotiations.

2. The haircut must be substantial to be credible . An 18% haircut (Ethiopia) is clearly insufficient to restore debt sustainability, as private creditors understood when they rejected the offer. Ghana's 37% haircut, while painful, restored confidence and allowed for a swift conclusion.

3. Coordination with the IMF is essential . Ghana's success was based on a robust $3 billion IMF program, which provided the credible macroeconomic framework necessary for negotiations. Without an IMF program, as is currently the case for Senegal, creditors have no assurances regarding adjustment policies and future sustainability.

A possible modus operandi for Senegal

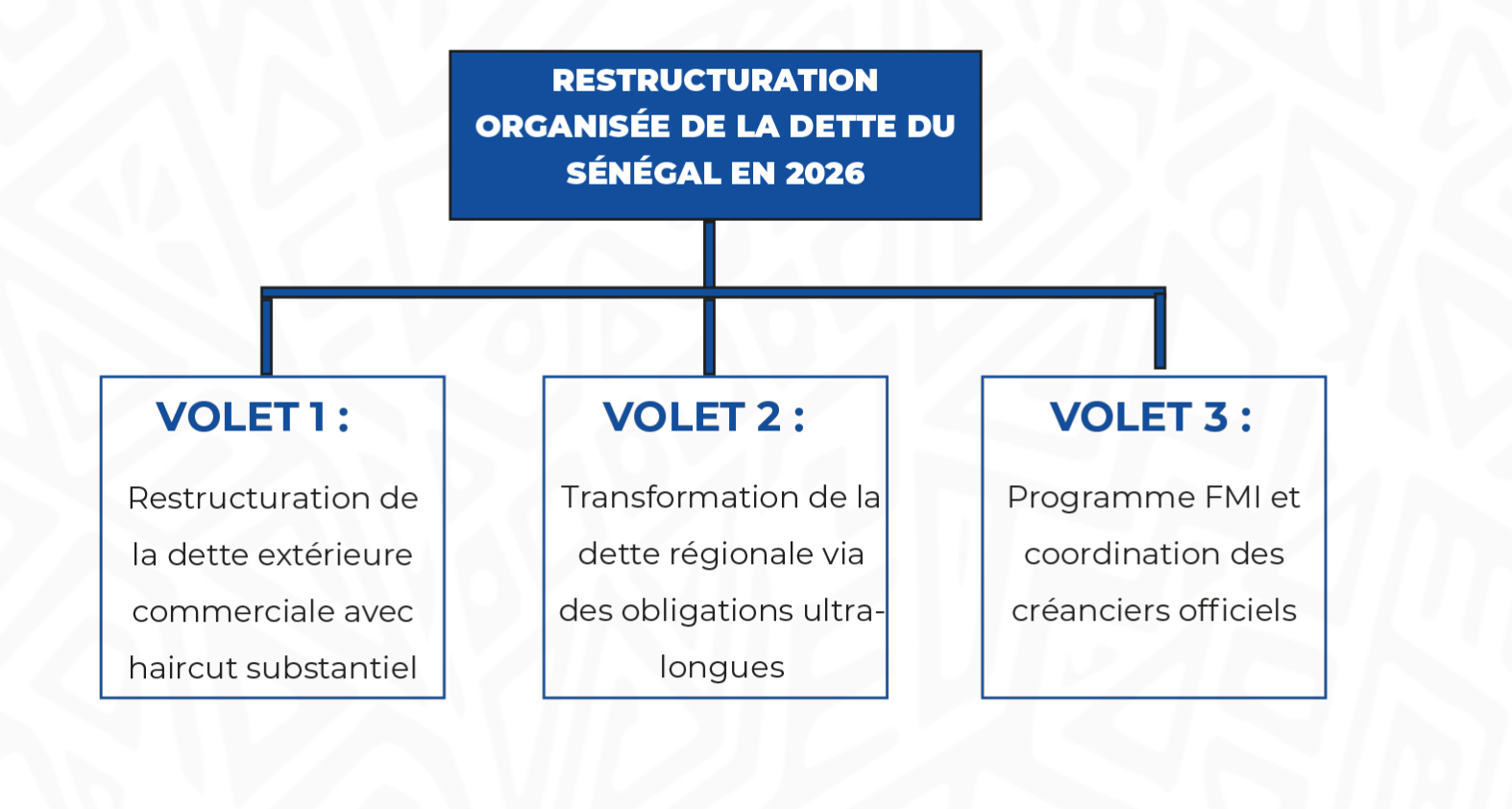

Based on macroeconomic analyses and international lessons learned, we recommend this roadmap structured in three parts.

Restructuring of external commercial debt with substantial haircut

External commercial debt, representing 38% of total external debt (approximately $18 billion or 10 trillion CFA francs), must be given priority. This debt includes Eurobonds (approximately one-third) and commercial loans from major players such as Standard Chartered, MUFG, and Cargill. Proposed restructuring parameters:

• Haircut: 50-60% on principal and accrued interest . This level, higher than the Ghanaian haircut of 37%, reflects Senegal's more deteriorated situation: a debt-to-GDP ratio of 132% (compared to 88% for Ghana before restructuring), the absence of an ongoing IMF program, and the scale of financing needs in 2026.[3][1]

• Extension of maturities : restructuring of maturities over 10-15 years with a grace period of 3-4 years on the repayment of the principal, allowing Senegal to pass the peak of 2026 and to benefit from the oil and gas revenues expected from 2027.

• Reduced coupons : interest rates of 4-5% in the first years, then 5.5-6% thereafter, aligned with regional standards and lower than current market rates reflecting the Senegalese risk premium.

• Options for creditors : like Ghana, offer a DISCO option (with high haircut but faster repayment) and a PAR option (without haircut but very long maturity and reduced coupon), offering flexibility to different investor profiles.

Justification for a 50-60% haircut:

The Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) conducted by the IMF in 2023 classified Senegal as being at moderate risk of external and overall debt distress. However, this analysis was based on the assumption of a convergence of the budget deficit towards 3% of GDP (WAEMU criterion) and the start of hydrocarbon production. The revelation of the hidden debt (an additional 132% of GDP) and the failure of the IMF program invalidate these assumptions.19

To bring the debt-to-GDP ratio down to a sustainable level of around 70% (the WAEMU threshold for countries with high repayment capacity), and given a nominal GDP of approximately 23 trillion CFA francs, a debt reduction of around 12.4 trillion CFA francs (62% of GDP) is necessary. With external commercial debt of around 10 trillion CFA francs, a 50-60% haircut would generate a reduction of 5 to 6 trillion CFA francs, or about half of the required adjustment. The remainder would come from the restructuring of domestic/regional debt and fiscal adjustment.[25]

Transformation of regional debt through ultra-long bonds

The EPA mechanism must be strengthened and systematized to convert all problematic bank debt into sovereign bonds with sustainable conditions.

Suggested parameters:

• Ultra-long maturities: 10-15 years , drastically reducing short-term refinancing pressure and smoothing the amortization profile.

• Rates close to the BCEAO marginal lending rate: the BCEAO marginal lending window rate is currently at 5.25%20. The new regional bonds could be issued at rates of 5.5-6%, slightly above the marginal rate but well below the 8.47% recently observed on the December auctions.

• BCEAO Guarantees: explore the possibility of a partial guarantee mechanism from the BCEAO or a liquidity facility for these bonds, reassuring commercial banks about their ability to mobilize these securities if needed.

• Gradual conversion : spread the conversion over 18-24 months to avoid a sudden saturation of the regional market and allow banks to adjust their portfolios in an orderly manner.

Use of mobilized resources:

The funds raised through these restructured EPAs would be allocated primarily to the repayment of bonds maturing in 2026-2027, notably the SOGEPA Sukuk. Issued in April 2022, this 330 billion CFA franc Sukuk comprises three tranches: 7 years (55 billion at 5.80%), 10 years (55 billion at 5.95%), and 15 years (220 billion at 6.10%). The 7-year tranche matures in 2029 but already requires semi-annual payments of principal and interest. On October 29, 2025, a payment of 14.73 billion CFA francs was made. Ensuring the continuity of these payments is crucial to maintaining the confidence of the regional Islamic market, a rapidly growing segment in which Senegal has positioned itself as a pioneer.

Expected results:

• Lower domestic debt cost : by moving from auction rates of 8.47% to rates of 5.5-6%, the annual savings on interest would be in the order of 200-250 billion FCFA for a stock of domestic debt of 7,500 billion FCFA.

• Extension of average maturity : the average maturity of domestic debt would increase from 5-6 years currently to 8-10 years, reducing the refinancing risk.

• Preservation of banking space : by avoiding excessive accumulation of short-term debt, banks would regain a capacity to lend to the private sector, essential for economic recovery.

IMF program and coordination of official creditors

No credible restructuring can succeed without a robust IMF program that defines the macroeconomic framework, adjustment policies, and financing needs. Senegal must quickly conclude its ongoing negotiations with the IMF to secure a new program, ideally a combined Extended Credit Facility (ECF) and Extended Fund Facility (EFF), for an amount of $2-3 billion over 3-4 years.

Key elements of the IMF program:

• Gradual fiscal adjustment : convergence of the budget deficit from 7.8% of GDP in 2025 to the WAEMU criterion of 3% by 2027-2028, through a combination of revenue mobilization (broadening of the tax base, reduction of exemptions) and rationalization of expenditure (energy subsidies, payroll, restructuring of agencies).[2]

• Structural reforms : improved public debt management, strengthened governance of state-owned enterprises, budget transparency (regular publication of debt data), and energy sector reform. • Nominal peg: maintaining the CFA franc's peg to the euro through the BCEAO mechanism, providing essential monetary stability to restore confidence.

Coordination with official creditors:

Bilateral creditors (representing 19% of external debt, or approximately $9 billion) will need to be involved within the framework of the Paris Club or, for non-member creditors such as China, via the G20 Common Framework. China demonstrated its ability to work within this framework during the Zambian restructuring, accepting the principle of "comparability of treatment."22 A 40-50% net present value debt relief on official bilateral debt, comparable to the terms obtained by Ghana and Zambia, would generate relief of $3.6 to $4.5 billion (2 trillion to 2.5 trillion CFA francs), significantly contributing to restoring sustainability. An ambitious but realistic timetable, modeled on Ghana's completion of its Eurobond restructuring in 18 months, is achievable. According to our estimates, the key to success lies in the immediate launch of the process, as early as January 2026, to prevent the March 2026 crisis from degenerating into a disorderly default.

The specter of the Lebanon scenario in the event of a disorganized restructuring

The lack of organized restructuring exposes Senegal to the risk of a Lebanese-style scenario, the economic, social, and institutional consequences of which would be catastrophic. The Lebanese experience of March 2020 serves as a textbook example of what must be avoided at all costs, especially for Senegal in March 2026.

Chronology and anatomy of the Lebanese defect

On March 7, 2020, the Lebanese government announced its inability to meet a $1.2 billion Eurobond payment due on March 9, marking Lebanon’s first sovereign default. This decision followed a depletion of foreign exchange reserves, which the Prime Minister described as “worrying and dangerous.” Further payments were due: $700 million in April and $600 million in June 2020. The default quickly spread to the entire $32 billion stock of Eurobonds, constituting what analysts termed a “hard default”—a default without structured negotiations with creditors, a clear restructuring plan, or a credible macroeconomic adjustment program (23). Lebanese banks alone held $12.7 billion of these Eurobonds (40% of the total) in January 2020, while the Central Bank held $5.7 billion. This domestic concentration transformed sovereign default into an instant systemic banking crisis (24).

The devastating economic consequences

Lebanon’s disorganized default in March 2020 triggered a catastrophic economic collapse, with a 2,158% depreciation of the currency and a 20% drop in GDP. A few examples illustrate the scale of the Lebanese disaster. Currency collapse: The exchange rate of the Lebanese pound plummeted from 1,507 LBP/dollar (official rate) to 34,000 LBP/dollar on the black market between early 2020 and 2022, representing a depreciation of 2,158%. This hyperinflation wiped out the population’s savings and destroyed purchasing power (25).

Brutal economic contraction : Lebanon’s GDP fell from $55 billion in 2019 to $44 billion in 2020, a contraction of 20% in a single year. The World Bank described this crisis as a “deliberate depression,” emphasizing that it resulted from political choices—or the lack thereof—rather than from inevitable economic forces (26).

Hyperinflation : Between October 2019 and February 2020, consumer prices exploded by 580% (27), reducing households' ability to meet their basic needs to nothing.

Job losses and business closures : Between September 2019 and February 2020, 785 restaurants and cafes closed, resulting in the loss of 25,000 jobs. These figures only concern one sector over a five-month period, suggesting much more widespread job losses across the economy.

Paralysis of the banking system : Faced with an anticipated bank run, Lebanese banks unilaterally imposed draconian restrictions on dollar withdrawals, establishing de facto capital controls outside of any legal framework. These measures shattered confidence in the financial system and disrupted payment systems, with many international banks restricting transfers to and from Lebanon.

Rating downgrade : Lebanon's sovereign debt has been downgraded to "junk" status, permanently closing off access to international capital markets.

Inflationary spiral through monetization : To fill the funding gap created by the default, the Central Bank of Lebanon (BDL) was forced to massively print Lebanese pounds, fueling hyperinflation that drove the exchange rate from 2,000 LBP/$ in early 2020 to 34,000 in 2022, with no end in sight. This monetization created a vicious cycle: the more the BDL printed, the more the currency depreciated, the faster inflation accelerated, and the worse the funding gap became.

Strategic mistakes to avoid

A retrospective analysis of the Lebanese case identifies several fatal errors that Senegal must absolutely avoid:

Mistake #1: Lack of a restructuring plan before default . Lebanon defaulted without having prepared a credible proposal for its creditors, without an IMF program, and without a macroeconomic adjustment framework. This lack of vision created total uncertainty, paralyzing any possibility of constructive negotiation.

Mistake #2: Lack of engagement with creditors . After the March 2020 default, Beirut showed little interest in addressing the consequences, allowing the situation to deteriorate without active negotiation. This passivity transformed a liquidity crisis into a profound solvency crisis.

Mistake #3: Hasty sale of assets by local financial institutions . Between January 2019 and March 2020, Lebanese banks sold up to $4.7 billion of Eurobonds to foreign creditors, exacerbating the depletion of foreign exchange reserves and shifting the risk onto less patient players. Shockingly, even the Central Bank insisted on honoring a $1.5 billion Eurobond payment in November 2019, despite knowing that reserves were critically low.

Mistake #4: Premature disclosure of difficulties. In 2019, the Lebanese Finance Minister shared a confidential memo about a potential debt restructuring not with his team, but with the press, more than a year before the default. This leak triggered an immediate downgrade by Moody's and precipitated the crisis, illustrating the crucial importance of confidentiality in the preparatory phases.

Similar precursor signals in Senegal

Without being a Cassandra, several indicators show that Senegal is on a trajectory similar to that of pre-default Lebanon, justifying urgent action:

Signal 1: Massive discounts on sovereign bonds . Senegalese Eurobonds are trading at discounts of 40-49%, comparable to the levels observed in Lebanon before its default. More worryingly, bonds maturing in February 2026 are trading at a 20% discount, signaling that even very short-term maturities are no longer considered safe by the markets.

Signal 2: Rationing on the regional market. The dramatic drop in appetite for Senegalese tenders on the WAEMU market – with only 35 billion raised out of 95 billion requested in December 2025 – is reminiscent of the drying up of bank financing experienced by Lebanon.

Signal 3: Tension in the banking system . The downgrade of the Senegalese banking system's rating to CCC+ by Fitch, combined with a non-performing loan rate of 10.6%, indicates increasing fragility that could degenerate into a systemic crisis in the event of a sovereign default.

Signal 4: Cascading downgrades by agencies . Senegal suffered three downgrades in 2025 (Moody's, Fitch, S&P), following a trajectory similar to Lebanon, which had experienced a series of downgrades before its default.

Signal 5: Rising domestic interest rates . The 158 basis point jump in auction rates in one month (from 6.89% to 8.47%) reflects a growing risk premium, a precursor to possible full credit rationing.

The fundamental lesson from Lebanon for Senegal is clear: a disorganized default is not simply a financial crisis; it is a total economic and social catastrophe that destroys decades of development in a matter of quarters. The human cost—measured in lost jobs, wiped-out savings, and increased poverty—far outweighs the short-term gains of debt non-payment. Organized restructuring, however painful, preserves what is essential: confidence, institutions, and the capacity for recovery.

Conclusion

Senegal is at a crossroads; indeed, no expression has ever been more apt. March 2026 is no longer a distant horizon, but an immediate deadline—in less than three months—that will determine the country's economic and social trajectory for the coming decade. The figures are stark: debt service of 747 billion CFA francs in a single month, Eurobonds trading at 50 cents per dollar, a financing gap of 6,075 billion CFA francs for 2026, and public debt reaching 132% of GDP.

In this context, the probability of avoiding a restructuring of Senegal's public debt is virtually nil. The question is therefore no longer whether Senegal should restructure its debt, but how this restructuring will be carried out. Two paths lie before Senegalese policymakers, with diametrically opposed consequences. The first path, that of a disorganized default, leads inexorably to the Lebanese scenario: monetary collapse, a 20% economic contraction, hyperinflation, job losses, banking paralysis, and lasting exclusion from international markets; even if this scenario could be mitigated by the social safety net of membership in the WAEMU zone. Lebanon, five years after its March 2020 default, has still not finalized a restructuring with its creditors, remains mired in a major humanitarian crisis, and has seen its economy reduced by half.

This catastrophic scenario is not the result of economic inevitability, but of political choices—or lack thereof: default without a plan, the absence of negotiations with creditors, and the refusal of necessary macroeconomic adjustments. The second path, that of organized restructuring, is inspired by the Ghanaian model: a comprehensive approach covering both external and domestic debt, a substantial 50-60% haircut on external commercial debt to restore sustainability, a transformation of regional debt through ultra-long, low-interest bonds, and a robust IMF program anchoring adjustment policies.

This path is undoubtedly painful for both creditors and Senegalese citizens. It entails budgetary sacrifices, structural reforms, and a temporary loss of sovereignty over certain economic policy choices. But it preserves the essentials: macroeconomic stability, the confidence of partners, future access to financing, and above all, the ability to protect the most vulnerable segments of the population. Since April 2024, the Senegalese authorities have demonstrated a remarkable commitment to transparency, courageously disclosing the hidden debt despite the political repercussions. This transparency, praised by the IMF and international partners, constitutes a valuable asset of trust that must now be leveraged to negotiate a fair and sustainable restructuring. Creditors, aware of the gravity of the situation, have demonstrated in other contexts (Ghana, Zambia) their capacity to accept substantial concessions when a credible negotiating framework is offered.

Economic history teaches us that sovereign debt crises, however severe, can be overcome when addressed with courage, transparency, and a methodical approach. Ghana, following its 2023-2024 restructuring, has returned to a positive growth trajectory and gradually restored its access to markets. Zambia, despite a longer process, is seeing its economy rebound, with projected growth of 6% in 2026. These examples demonstrate that a well-managed restructuring is not the end, but the beginning of recovery.

For our beloved country, Senegal, a stable and democratic nation with strong institutions and promising oil and gas resources, the success of an organized restructuring is virtually guaranteed. However, this success requires immediate political action and decisive leadership. The completion of debt management reform and the full implementation of the remaining corrective measures, as emphasized by the IMF, will be essential to definitively resolve the issue of hidden debt and sustainably restore investor confidence. The coming weeks will determine whether Senegal chooses the path of structured recovery or that of disorganized chaos. Senegalese citizens, creditors, and the international community expect the authorities to choose responsibility over expediency, and foresight over denial.

The time to act is now.

Commentaires (3)

Les seuls responsables de cette situation catastrophique du Sénégal sont Macky Sall et ses alternoceurs qui ont pillé les deniers publics, ont fui le pays et qui continuent de nous narguer parce que Diomaye ne veut pas faire son travail.

Dans tout pays sérieux avec un Président honnête qui respecte sa parole, on devrait tous les voir en prison et des mandats d'arrêts internationaux et demandes d'extradition lancés partout dans le monde pour aller les chercher mais que nenni, ils sont tous en liberté et ceux qui ont été convoqué ont été relaché avec des bracelets électroniques.

Finalement, tous ces bracelets commandés par le régime de Macky faisaient partie du complot car Macky savait que certains de ces alternoceurs corrompus seraient convoqués par la justice et qu'il fallait leur trouver une porte de sortie.

Diomaye va tous les libérer et tant pis pour les morts tués par le régime mafieux de Macky et tant pis pour nos deniers publics, pour notre foncier et pour tous les pauvres sénégalais victimes de la politique désastreuse de Macky durant ses 12ans de règne.

Diomaye a trahi et poignardé les sénégalais mais il le paiera très chers car il y'aura tôt ou tard une justice pour les jeunes tués par le régime de Macky et on y rajoutera la traitise de Diomaye et de tous ceux qui profitent actuellement du systéme mafieux qui s'est regénéré sous une autre forme.

La CREI était pour Wade et ses alternoceurs, l'OFNAC pour Macky et ses alternoceurs et le PJF (Pool Judiciaire Financier) pour Diomaye et ses néo-alternoceurs. Un jour viendra et les sénégalais auront enfin une justice qui traduira tous les corrompus !

Participer à la Discussion

Règles de la communauté :

💡 Astuce : Utilisez des emojis depuis votre téléphone ou le module emoji ci-dessous. Cliquez sur GIF pour ajouter un GIF animé. Collez un lien X/Twitter, TikTok ou Instagram pour l'afficher automatiquement.